By Dick Scruggs

August 28, 2021

Originally published in the Mississippi Free Press

Smith was working then to get local Black people to use absentee ballots to support challenger Joe Brueck for the Beat 5 supervisor’s race against incumbent J. Hughes James, both white men. Voting absentee, they wouldn’t be hassled at the polls.

That Saturday, Smith took his latest batch of absentee ballots to drop off as he drove downtown. At the courthouse, he walked up to the steps where he encountered three white men. They tried to block him, telling Smith he could not enter, and he argued back, leading to a physical altercation.

Suddenly, prosecutors would later say, a man named Noah Smith pulled out his .38-caliber pistol and shot Smith in the ribs under his right arm at close range. Ditney Smith stumbled and then fell into bushes, where he soon died. He then was left lying on the ground for several hours.

Sheriff Bob Case saw Noah Smith leaving covered with blood. He soon learned that Mack Smith and Charles Falvey were with Noah when they stopped him. All these suspects lived in Beat 5 in the Loyd Star community out in the county toward where Ditney Smith lived and farmed.

Despite efforts by two district attorneys, E.C. Barlow in 1955 and the newly elected Mike Carr in early 1956, the three prime suspects never went to trial because not a single witness would agree to testify. Now all three accused men are dead.

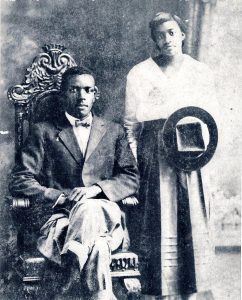

But it is not too late for the community to commemorate the life of businessman and veteran Ditney Smith and memorialize his death in a respectful way.

To that end, I am supporting an effort underway in Brookhaven to erect a historical marker that both honors Ditney Smith’s courage and acknowledges the brutal manner of his death. Thanks to the efforts of his descendants, a nationwide movement to memorialize lynchings, and local Brookhaven citizen groups, a promising biracial coalition, including myself, is seeking the approval of the Lincoln County Board of Supervisors to place a historical marker on the courthouse lawn where Smith died.

‘Some Race Trouble’ Downtown

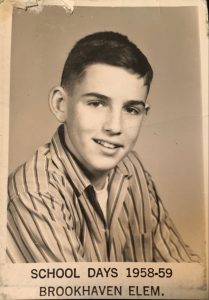

Lamar Smith’s unresolved, unacknowledged murder has always haunted me. I was a boy of 9 growing up in white Brookhaven when, first, Smith was killed and then two weeks later on Aug. 28—66 years ago today—Emmett Till was murdered in the Delta.

On Aug. 13, 1955, like most summer Saturdays, I was about to ride my bike to the show—the movies at the Haven Theater on West Cherokee Street—when my mother got a phone call. She then told me I couldn’t go. When I pleaded for a reason, she said on account of “some race trouble” downtown.

After pressing her for more, she finally told me there’d been a “lynching at the courthouse.”

I thought that meant that someone had been hanged, but she said no, that some men “from out in the county” had shot a colored man. The “county” phrase had special significance to me, because the kids I was in grade school with at Brookhaven Elementary “from out in the county” were somehow meaner and rougher than the in-town kids I usually played with.

Like adults in Brookhaven I know who kept quiet about witnessing Ditney Smith’s murder, I was afraid of people “from out in the county.” I still am.

A Way to Help Heal and Educate

To this day, neither my hometown nor Lincoln County has honored or even publicly remembered the bravery and determination of a man who stood up for the ideal that all Americans are created equal. His execution at a place where laws were supposed to protect the county’s citizens occurred in the presence of numerous bystanders who customarily gathered around the courthouse on Saturday mornings; many are probably dead now.

The FBI later estimated that there were 50 to 75 potential witnesses, and not one would testify about what they saw, shamefully denying witnessing the crime. The FBI reopened the Lamar Smith case in 2008 as part of a new cold-case initiative for unresolved civil rights-era murders. The agency examined the evidence and confirmed the identity of the three suspects—Smith, Smith and Falvey—but closed the case in 2010 because all three had died.

This means real justice is not possible for Ditney Smith, but that does not mean his memory should die. The Brookhaven Daily Leader wrote in January 2020 that the Lamar Smith case must be remembered: “Some in Brookhaven would prefer to forget parts of its past, including the Smith murder. But in doing so, we are choosing to ignore a key piece of the state’s civil rights history. We are also choosing to diminish the sacrifice Smith made so that black voices would count.”

People must come together so the effort to erect a marker to Smith on the courthouse grounds will be successful. It may be especially challenging because relatives of two of the three men arrested for Smith’s murder presently hold influential political offices. But I still believe this can happen.

Please join this effort if you can. It’s important, and it’s time that we get this done. As the Daily Leader wrote last year, “Don’t ignore the past, even when it’s painful.”

Also read what Donna Ladd discovered about Lamar Smith murder, his murderers and other lynchings in Brookhaven, in her in-depth historic piece on his murder, “Buried Truth: Unresolved, Disregarded Lamar Smith Murder Haunts Lincoln County.“

Learn more about Lamar “Ditney” Smith in MFP Advisory Board member Keith Beauchamp’s documentary, “Murder in Black and White: Lamar Smith” and more about Emmett Till in “The Untold Story of Emmett Louis Till.“

No comments:

Post a Comment