by Pete Welding

Howlin' Wolf, the powerful Mississippi born singer who was one of the major shapers of the electrically amplified modern blues style that has been so dominant an influence on all popular music since his time, died January 10, 1976, of complications arising from a kidney disease for which he was being treated. At the time of his death he was 65 and had been active as a blues performer for more than four decades, first as an itinerant singer-guitarist at simple back country entertainments in his native Mississippi and Arkansas, and from the late 1940s as a recording artist, radio per-former, and leader of one of the first electric blues ensembles to achieve national prominence.

For the last 25 years of his life he was one of the foremost and greatly respected blues artists resident in Chicago, where he had moved in '1952 after signing an exclusive recording contract with that city's Chess Records, for which he made his finest recordings and continued to record until the recurring illness of his final years forced him to curtail much of his performing and recording activities. Still, despite several heart attacks and a kidney illness of such severity that he required regular dialysis treatment and heavy medication, Howlin' Wolf did not give up performing entirely, and he invariably made his scheduled concert appearances.

Like most of the performers of the early postwar period, Wolf was fundamentally a traditional Mississippi blues musician, a spell-bindingly powerful singer, guitarist, and harmonica player whose strongest and most durable musical allegiance over a long profession-al career was to the traditional blues of the Southern countryside where he had been born, raised and first drawn to music. Many of Wolfs early recordings derived in fact from the work of older musicians he had encountered in the Mississippi Delta region, most notably his mentor Charley Patton, and, as do few recordings of the postwar period. they possess a sense of dark power and naked emotional force that are almost overwhelming in their intensity. Typical of this approach are recordings such as

Saddle My Pony (learned from Patton and recorded in 1948);

Moanin' At Midnight,

How Many More Years and

Dog Me Around (from 1951);

Baby How Long,

No Place To Go and

Evil Is Goin' On (all from 1954 Forty-Four (1955);

Smokestack Lightnin' and

I Asked For Water (from 1956), and

Who's Been Talkin'?,

'Moanin' For My Baby,

Tell Me and

Sittin' On Top Of The World (all recorded in 1957), among others. His wry, vinegary harmonica playing, more rural in orientation than that of virtually any other postwar player of the instrument, is heard on just about every one of these performances, for he tended to feature harp on his most country-styled songs, though not exclusively so, and he continued to utilize it throughout his recording career.

Additionally, a number of his performances were organized on scalar and modal rather than on harmonic principles as, for examples, Moanin' At Midnight, Riding In The Moonlight, Crying At Daybreak, Smokestack Lightnin', No Place To Go, I Asked For Water and Moanin' For My Baby—an approach that is typical of some of the older forms of Mississippi and Deep South blues and which permits the projection of a particularly forceful rhythmic base of hypnotic intensity. On numbers of this sort Wolf frequently employed to striking effect a wordless moaning and falsetto melisma, giving his recordings a highly distinctive character as a result.

In light of his early background as an exponent of the blues of his native state, the strong, sustained traditional bias of Wolfs music is explicable. He was born Chester Arthur Burnett on June 10, 1910, in West Point, near Tupelo, Miss.. and as a young teenager moved. in 1923, to Ruleville, in the heart of the Mississippi Delta. It was while living in this cotton-producing area, where his parents were employed on Young and Mara's plantation, that Wolf was first drawn to music, his inspiration being the great Delta singer and guitarist Charley Patton who lived on the nearby Dockery's plantation.

"It was he who started me off to playing," Wolf recalled. "He showed me things on the guitar, because after we got through picking cotton at night, we'd go and hang around him, listen at him play. He took a liking to me, and I asked him would he learn me, and at night after I'd get off work I'd go and hang around.

He used to play out on the plantations, at different one's homes out there. They'd give a supper, call it a 'Saturday night hop' or some-thing like that. There weren't no clubs like nowadays. Mostly on weekends they'd have them. He'd play different spots., he'd be playing here tonight and somewhere else the next night, and so on. He mostly worked by himself because his way of playing was kind of different from other people's. It took a good musician to play behind him, because it was kind of off-beat and off-time but it had a good sound the way he played. I never did work with him because he was a traveling man. In the spring of the year he'd be gone; he never came in until the fall. He followed the money. He couldn't make too much money in Mississippi in the spring of the year because people didn't have any money until harvest time. He'd always conic back in the fall.

"I felt like I got the most from Charley Patton and Lemon Jefferson—from his records, that is. He came through Mississippi, in different areas, but I never did see him. What I like about Lemon's music most was that he made a clear chord. He didn't stumble in his music like a lot of people do—plink! No, he made clear chords on his guitar, his strings sounded clearly. The positions he was playing in—that made his strings sound clear. There wasn't a smothered sound to his chords. As a kid I also heard records by Lonnie Johnson, Tampa Red and Blind Blake—they played nice guitar. heard tell of Tommy Johnson too but I never did see him.

"After Charley started showing me guitar I came along slow. I didn't really pick up my time—didn't get that right—until somewhere in the '40s. I got my first guitar in 1928. My father bought it for me before we left Ruleville. We were living out there on the Quiver River, on Boosey's plantation...At that time I was working on the farm with my father, baling hay and driving tractors, fixing fences, picking cotton and pulling corn....It was in the late 1920s when 1 decided to go out on my own. to go for myself. 1 just went running 'round through the country playing, like Charley and them did. ... Just all through the cottonbelt country, and mostly by myself. I was just playing blues and stuff like that. Some of the first things I learned how to play was How Many More Years and Smokestack Lightnin', just common songs you heard down there. When I started playing guitar and blowing my harp, anything come to mind I'd just sing it and rhyme it up and make me a song out of it. Mostly I'd just take things 1 heard from people round there. I just picked up music, just playing guitar. I mostly just stayed in the country farming.

"It was Sonny Boy Williamson—the second one, Rice Miller—who learnt me harmonica. He married my sister Mary in the '30s. That's when I met him. He was just loafing around, blowing his harp. He could blow though. But he lived too fast; he was drinking a lot of whisky and that whisky killed him. Sonny Boy showed me how to play. 1 used to strum guitar for him. See, he used to come there and sit up half the night and blow the harp to Mary. I like the harp, so I'd fool around and while he's kissing Mary I'd try to get him to show me something, you know. He'd grab the harp and then he'd show me a couple of chords. I'd go around the house then, and I'd work on it.

"It was somewhere around this time that 1 met Robert Johnson. Me and him played together, and me and him and Sonny Boy—Rice Miller—played together awhile...I worked a little while with him around through the country; we was playing around Greenwood. Itta Bena and Moorhead Mississippi). We didn't stay together too long because I would go back and forth to my father and help him in the farming. 'Cause I really wasn't ready for it—the music, you know. At that time I couldn't play near as well as he could; I'd just be hanging around trying to catch onto something. Rice, though, he could play with him. We took turns performing our own tunes. If I played lead and sang, they'd back me up, see, 'cause at that time I wasn't good enough to back them up.

"I don't know how long Robert had been playing when I met him but at that time he was playing nice...I believe Son House mostly taught him because, Son and Willie Brown, I used to play a little with them. I worked with the two of them at some of those Saturday night hops. They was playing music for dancing mostly, fast numbers to dance to. That's the only time those people would have a chance to enjoy themselves—on a Saturday night or a Sunday—'cause those landlords would want them to work any other time.

"When I'd go out on them plantations, the people played me so hard. They look for you to play from 7 o'clock in the evening until 7 o'clock of the next morning. That's too rough! I was getting about a dollar and a half and that was too much playing by myself. People would yell, 'Come on, play a little, baby!' A bunch would come in and they was ready to play and dance. So I decided I would get a band, get two or three more fellows to help me out, but I didn't do that until 1948. Some of the jobs I had taken was 50 cents a night, back in Hoover's days. Seven in the evening 'til seven the next morning."

Wolf continued this life of farming and occasional or part-time performing until he was inducted into the Army in 1941 . He remained in the service for the duration of the war, spending much of his tour stationed in Seattle, Wash. He returned to Mississippi and farm work in 1945, later rejoining his father on a plantation in Arkansas. After two years of farming on his own in Penton, Miss., he moved to West Memphis, Ark.

"It was there." he recalled, "in 1948, when I formed my first band and began to follow music as a career. On guitars I had Willie Johnson and M. T. Murphy. Junior Parker on harp, a piano player who was called Destruction [Bill Johnson]--he was from Memphis, and I had a drummer called Willie Steele. We played all through the states of Arkansas. Alabama, Mississippi and Missouri. The band was using all electric, amplified instruments at that time. After I had come to West Memphis I had gotten me an electric guitar. I had one before I went into the Army and when I came out 1 bought another one. I was broadcasting too, on a radio station in West Memphis, KWEM. It came on at 3 o'clock in the evening I afternoon. It was in '49 that I started to broadcast. I produced the show myself, went around and spoke to store owners to sponsor it, and I advertised shopping goods. Soon I commenced advertising grain, different seeds such as corn, oats, wheat. then tractors, tools and plows. Sold the advertising myself, got my own sponsors."

Wolfs regular radio broadcasts were extremely helpful in creating a demand for the music of his group, and he began to perform widely through the Deep South. Also helpful were recordings, for at about the same time he began making records, his earliest sides being made in Memphis for the then newly established Sun Records operation of Sam Phillips. The recordings—which included Saddle My Pony, Worried All The Time, Moanin' At Midnight, How Many More Years, Howlin' Wolf Boogie, My Last Affair, Oh! Red, and others—were issued as singles on Chess Records, the Chicago-based independent to which Phillips was providing master recordings. At much the same time Wolf was recording for RPM Records through the agency of the young Ike Turner. who was serving as talent scout and record producer for the West Coast label. As a result of the success he enjoyed with Moanin' At Midnight/How Many More Years (Chess 1515), Wolf was signed to an exclusive recording contract with Chess and, following a second recording session for them in Mem-phis, he moved to Chicago late in 1952, where he made his home for the rest of his life.

The move was to prove beneficial to the development of his music. With few exceptions his Memphis-made recordings were not particularly distinguished, at least when com-pared with the strong, well-focused recordings he soon was making under the direction of

Leonard Chess. As a result of his recording of Muddy Waters and others. Chess had developed a real understanding of rural-based modern blues of the type Wolf performed so well, and he lavished considerable care and attention to recording Wolf's music, providing him supporting musicians sensitive to its demands. It paid off' handsomely: Wolf's finest and most successful records, artistically as well as commercially, have all appeared on Chess Records.

After recordings had created a demand for his music, Wolf set about establishing himself on the busy competitive Chicago blues performing scene and put together a solid band of his own with which he began working the city's blues clubs. The most notable addition to his band was guitarist Hubert Sumlin, who under Wolf's tutelage and encouragement developed into one of the most consistently interesting and individualistic of all modern blues guitarists. From the start Sumlin has been one of the most important contributors to the distinctive, characteristic sound of Wolf's records. For the rest, Wolf employed Chicago musicians. drawing from the large reservoir of superior bluesmen resident there.

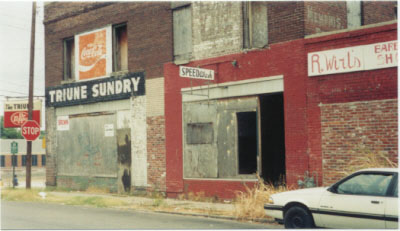

During the 1960s he settled in to a long stint at Sylvio's Lounge on Chicago's near West Side and for a number of years his was among the finest, most consistent and satisfying club presentations to be heard in the city. With regular employment, the personnel of his band remained considerably more stable and, consequently, the performance quality invariably higher than that of just about any other ensemble on the Chicago blues performing scene. And the live performances of his music were fully the equal of his recordings.

"Now, I don't consider myself a profession-al musician," Wolf observed. "I couldn't say I'm a professional 'cause I don't know too much about music, I'm just an entertainer: I can entertain pretty well in my way of doing. Before I became an entertainer, though, I sang for myself. Anything I set up and figured was good, I made up a song about it. I just watch people, their ways. I play by the movement of the people, the way they live. You see, every-thing that I sing is a story. The songs have to tell a story. See. if you don't put a story in there, people won't want to listen to it, because people mostly have been through the same emotions. Since I'm an entertainer, that's what I have to give the people who come to hear me, buy my records. I always tried to play a different sound from the other fellow ... have a good sound, to play something different. My music."

Howlin' Wolf left a rich legacy of music behind him. The best single introduction to his glorious Mississippi-based modern blues is provided by the low-priced 2-LP set Chester Burnett A.K.A. Howlin' Wolf (Chess 60016). His early RPM recordings have been collected on Howlin' Wolf Sings the Blues (Crown 5240), which also has been issued as Big City Blues (United 7717). Single LP al-bums on Chess include Moanin' In The Moonlight (Chess 1434), which later was issued as Evil (1540); Howlin' Wolf (1496); The Real Folk Blues (1502): More Real Folk Blues (151 2); Change My Way (418); Message To the Young (50002); Live And Cookin' At Alice's Revisited (50015); The Back Door Wolf (50045); The London Sessions (60008) and The Howlin' Wolf Album (Cadet Concept 319). He will be missed, and sorely too.

Honor his memory.