By Carl McIntyre

Jackson, MS Clarion Ledger

Sep 30, 1979

To the accompaniment of the diddley bow and a cane fife, the blues was born in the Mississippi Delta.

A musical form all its own, growing more popular the world over. the blues "was transplanted from Africa, reformulated and given English words," according to Alan Lomax, probably the world's foremost folklorist.

To prove his point, and to preserve the fading vestiges of the original blues singers for all time, Lomax has been in the Delta this year filming and recording.

"THE LAND WHERE THE BLUES BEGAN" is ready as a special for Mississippi Educational Television. It is being delayed for a time in order to see if it can be scheduled for a national audience on the Public Broadcasting System.

An hour long program, it just hits the high spots of Lomax' latest venture into American folklore. He re-corded and filmed more than 40 hours of the Delta blues, using as his "stars" some of the old timers who still remember the original verses as well as the tunes.

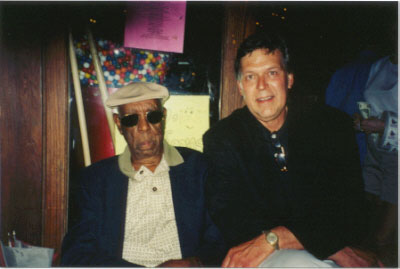

He features Sam Chatmon, Bud Spears, Jack Owens, Beatrice Maxwell, Lonnie Pitchford, Othar Turner, Clyde Maxwell, Lucius Smith and others. They range in age up into their 90s.

If listeners are able to understand all the words that some performers sing, there may be a hullabloo over the airing, for the blues had down to earth lyrics.

THAT'S WHAT MADE IT the blues, Lomax declares.

"It was music that gave vent to the emotions of people who expressed their frustrations, their ill treatment, their lack of hope in their singing," Lomax points out.

Shunted into a narrow world of their own, they knew mostly poverty. However, even their menial work they turned into a dance and the rhythmic motions were keyed to a melody. The words gave expression to their thoughts.

Life's basics were their themes. This can be under-stood by those who study the lyrics. One can see how they could almost rejoice in a love of living — or perhaps that is a living of loving.

From that, "Make me a pallet on your floor so your man will never know" or "Shakin' in the bed with me" came to be among the most popular of the ballads.

From that, "Make me a pallet on your floor so your man will never know" or "Shakin' in the bed with me" came to be among the most popular of the ballads.

LOMAX BELIEVES the blues was born in the Del-ta because of the isolation of the big groups of former Africans on large plantations. In their work and play they used music as a link to their past.

They had brought the "beat" as well as the body movements of the dance when they were uprooted from their homeland. In a new environment they applied their innermost emotions in a natural adjustment to a completely new way of living.

Even the dull. tiring, sweating task of hoeing a cot-ton patch became a dance and the hoes sounded a beat as they, almost in unison, were swung to the ground in a musical cadence. The words just came naturally. They expressed their resentments as well as their desires.

IT WAS THE SAME if they were choppin' down trees. There was a beat to the striking of the axes. When called upon to carry heavy loads, their labor became lighter as they virtually danced in step to a home grown ballad.

Those songs have lingered, but today the old words are giving way to new ones, and the younger generation is learning different verses while the melody lingers on.

Lomax had decided, from more than 40 years of study, that the blues had come from the cotton fields along the Mississippi River. He had recorded some of the music, as his Mississippi-born father had before him, but they had not filmed it, and they had missed some of the original lyrics.

NOW, WITH 40 HOURS of filmed music, the Archives of American Folklore, which Lomax' father, John A. Lomax, founded at the Library of Congress, is richer. It already had dozens of tapes and records made by the Lomax team since the 1930s.

Alan Lomax can hardly remember when he was not interested in folklore.

His father made it his life's work, beginning with the cowboys along the Chisholm Trail. Later, he brought a young Alan with him to Mississippi and other Southern states to record the folk music of prisoners in several penitentiaries.

That was in 1933.

Since then, Alan has combed the world for its folk-lore and has recorded more than 4,000 songs in 400 cultures.

He spent years in England, Ireland and Scotland, and found that this music had been continued in America by the people of Appalachia.

THEN HE TRAVERSED Spain, Italy and on to the Near East, Far East, Central and South America, tracing patterns of music from varied sources, but finding each had its tendrils deep into another area.

From this, Lomax "invented" cantometrics and choremetrics, which today are the world's lone systems for classifying songs (canto) and dance (choreo). From his home base as a member of the faculty at Columbia University in New York City, he teaches these systems and continues the research that the family has pioneered. He shows how the music and dance of one people jumped thousands of miles to be found in a new environment, enjoyed by a foreign populace.

Musical instruments for the blues, Lomax has found, were home made. Most often they copied those that had been made by the Africa natives and used hundreds, even thousands, of years earlier.

The drum, of course, is recognizable anywhere. So is the pan (cane) pipe, which is universal.

THE DIDDLEY BOW is perhaps the unique instrument for American music although it is copied, after a manner, from a one stringed instrument used in Africa.

The Delta diddley bow had these parts: a piece of broom wire, a snuff box (the round one, not the flat one, about an inch in diameter and one and a half inches long) and the broken neck of a glass bottle.

To make one, the wire was nailed to a wall and the snuff box was placed under the wire. Then, running a finger up from the bottom, one flicked the wire until the proper pitch was found. At this point the wire was cut to that length, fastened to a board, the snuff box used as a bridge.

To play it, the strummer put the neck of the bottle around a finger on his left hand and used it to slide up and down the wire to change pitch. The right hand was the "twanger." With both hands in motion, each moving about as speedily as the other, the music burst forth.

WITH A PAN PIPE fife and a drum or two, it was an orchestra. Othar Turner's fife and drum band has played at many places over the states.

Later, of course, the guitar and the banjo were added, but these were not originals.

In the era between 1905 and the 1930s, Lomax believes the blues had not only their heyday but also their introduction to others outside the Delta.

Rivermen, as they were known, were without families. Homeless, they moved about freely looking for work. They carried their dancing patterns to their new jobs, and sang as they labored. In the evenings, they looked for the love and other emotions that had escaped them in the drudgery of their daytime tasks.

Their journeys took the blues to the outside world and opened the way for its acceptance as a new form. From there on it was the birth of the blues for all America — and the world.

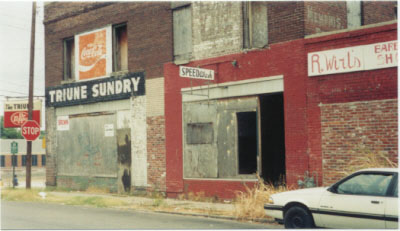

BACK IN THE DELTA. however, where it had all begun, it was still the home grown, completely unique musical form that had come into being a hundred years before. The environmental changes had altered it only slightly, reformed it into a new vehicle for a people's message.

As Lomax' film proves it now, the blues is still a North Mississippi phenomena — and one he enjoys. Watching the anthropologist with the fringed beard as he played back the tapes of his show, we wondered how he had ever stopped recording. He gets so wrapped up in the beat, so hip with the tunes it is with obvious difficulty that he sits quietly to edit the material. We fully expected him to jump up, imitating the dance and joining in the choruses.

His father, born near Clarksdale, was one of 21 children in the family which moved to Texas when he was but two years old.

THEIR TEXAS HOME WAS ON the Chisholm Trail and the cowboys passed by regularity. John Lomax was fascinated by their songs. By the time he was ten he had written down the words to dozens.

When he finally was able to enter Texas U. at the age of 32, he was so ready for an education that he graduated in two years. From there he went to Harvard and found a grant awaiting that let him tour the West with one of the early recording cylinders.

When he had all the cowboy music he felt necessary, he started with the blues. And this is when and where Alan came into the picture.

Now, 40 years later. Alan has no peer, at home or abroad, in the field of folklore.