Written by Arne Brogger

Original Title - "Ghost Story"

Original Title - "Ghost Story"

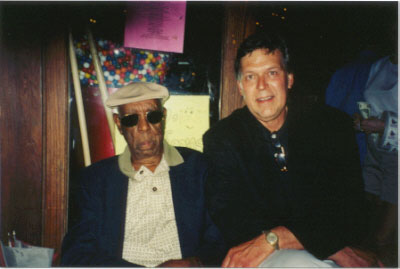

Business took me to Nashville for three days and I decided to take a long weekend and visit Memphis. I hadn’t been there in almost twenty years, not since the funeral of my old friend and co-conspirator, Walter “Furry” Lewis. Furry was a charter member of the Memphis Blues Caravan (MBC), a group of geriatric bluesmen whom I had the pleasure of booking and managing in the Seventies.

On a Friday morning I headed southwest out of Nashville on I-40 (The Music Highway, as the sign said) across the Tennessee River, through the rolling Cumberlands, on down to the brown and wide Mississippi. I had promised myself this trip for years. I had fantasized about it. Obsessed over it. It was like a reverse Vision Quest. I wanted to go back, to recapture scenes that had been an important part of my life, but knowing all the while that was not possible. Most of the folks I had known were now gone. But they had stayed with me – and I thought…who knows what I thought. I knew it was a trip I had to take.

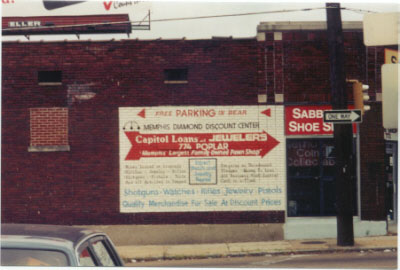

Capital Loans

I arrived early afternoon. The first stop was the Cozy Corner Café, BBQ ribs and chicken (with a side of beans), just to get in the right frame of mind. Then up Poplar Avenue to the intersection of Mannassas, where sat the global headquarters of Capitol Loans. Capitol was the pawnshop where Furry would hock his guitar every time he came off the road. When it was time to go back out again, it was up to me to “un-hock” it so that he could play the dates.

Turning on Mannassas I drove one short block to Mosby Street where Furry had once lived at number 811. The house is gone, having burned down a month before he died of complications from the fire. But standing next door was its duplicate. A four-room shotgun style house. Six or eight folks were sitting on the front porch. I asked if any of them knew Furry Lewis who used to live next door. An old woman volunteered, “the gittar picker?” I nodded. “You know he gone. Passed some time ago.” Yes, I know.

I looked over at the empty lot and remembered walking up on the porch, through the front door, into the main room where Furry sat on his bed. A whiskey glass stood on the table next to him covered by a saucer. “Spiders” he said, “can’t see too good. Don’t want no surprises.” That was in 1973.

Big Daddy’s Office

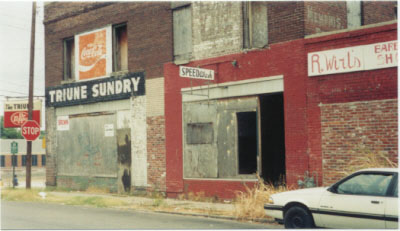

Bukka White’s “office” consisted of a chair leaned against a brick wall. Next to the chair was a wooden crate. Both sat on the shady side of the street beside Triune Sundry. This is where I first met him, having been told earlier by his wife that “Big Daddy ain’t home. He’s at his office.” Cruising the streets near Mosby, I knew it was around the area somewhere. Suddenly something told me to turn right at the corner of Leath. There it was.

Turning on Mannassas I drove one short block to Mosby Street where Furry had once lived at number 811. The house is gone, having burned down a month before he died of complications from the fire. But standing next door was its duplicate. A four-room shotgun style house. Six or eight folks were sitting on the front porch. I asked if any of them knew Furry Lewis who used to live next door. An old woman volunteered, “the gittar picker?” I nodded. “You know he gone. Passed some time ago.” Yes, I know.

I looked over at the empty lot and remembered walking up on the porch, through the front door, into the main room where Furry sat on his bed. A whiskey glass stood on the table next to him covered by a saucer. “Spiders” he said, “can’t see too good. Don’t want no surprises.” That was in 1973.

Big Daddy’s Office

Bukka White’s “office” consisted of a chair leaned against a brick wall. Next to the chair was a wooden crate. Both sat on the shady side of the street beside Triune Sundry. This is where I first met him, having been told earlier by his wife that “Big Daddy ain’t home. He’s at his office.” Cruising the streets near Mosby, I knew it was around the area somewhere. Suddenly something told me to turn right at the corner of Leath. There it was.

|

| Triune Sundry |

Triune Sundry

It was a hot day in 1973 when I had first stood on that corner and shook hands with a legend. He was B. B. King’s big cousin and had given B. B. his first guitar, a Stella. Muddy Waters would later tell me that there were licks Bukka did that he (Muddy) was still trying to figure out. And Bukka was the man who literally sang his way out of Parchman Farm Prison. I stood on the corner for a while. I took a few pictures. I could hear the rolling thunder of Aberdeen Blues and see his hands, hopping back on forth on the guitar. I got in the car and headed for Beale.

Daddy’s Dogma