"In the Delta, Blacks' Cemeteries were Plowed Under, Planted Over"

By Donna St. George

for the Philadelphia (PA) Inquirer

November 14, 1992.

In the sandy, soft soil on Bamboo Plantation, where a small black church buried its dead, there now grows a field of snowy-white cotton. Rev. Earnest Ware grew up here, in a community of black workers who made their living picking cotton and soybeans. They slept in shotgun shacks, and worshiped at their own church, and dug graves in the churchyard for their dead, maybe 100 or 200 people over a fifty year period. Since the 1960s, the community has disappeared along with the church and the graves. All that remains is cotton.

"It hurts," Mr. Ware says softly, thinking of his two little brothers, great-grandmother and great-uncle, whose caskets were buried in ground now tilled. "I go rolling by, and I look and think: After dying they didn't even have a decent resting place." Such desecration is not uncommon in the Mississippi Delta and perhaps beyond. As plantation communities have died out and people have moved away, farmers have sought to plant every possible acre of land. "It's terrible, but I would say it happens all the time," says Malcolm Walls, of the nonprofit Mississippi Action for Community Education (MACE), echoing the comments of several other community leaders as well the state's chief archaeologist, Sam McGahey. Some farmers don't know about the old cemeteries or mistakenly consider them abandoned, says James C. Cobb, a history professor at the University of Tennessee, author of a book on the Delta, The Most Southern Place on Earth. In other cases, Cobb says, the problem stems from "not putting a high premium on the places where black people are buried."

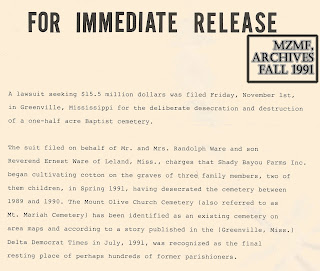

Just in the area near Bamboo plantation, people talk of two or three other cemeteries now plowed and planted. "It really does seem bad, but they sure do it," says Martha Thomas, 61, whose husband, A.T., was once the pastor at the Bamboo plantation church, Mount Olive Missionary Baptist, and now serves a nearby church. But Mr. Ware and his parents are among the first to take action. They filed a lawsuit last fall against the owners and farmers of Bamboo plantation, seeking $15.5 million in damages. They hope the suit will, at a minimum, deter other cemetery destruction. "It was only half an acre of land," laments Mr. Ware, 34, who was raised at the Mount Olive church and is now pastor of two others. "All that desecration for a measly half an acre."

"It hurts," Mr. Ware says softly, thinking of his two little brothers, great-grandmother and great-uncle, whose caskets were buried in ground now tilled. "I go rolling by, and I look and think: After dying they didn't even have a decent resting place." Such desecration is not uncommon in the Mississippi Delta and perhaps beyond. As plantation communities have died out and people have moved away, farmers have sought to plant every possible acre of land. "It's terrible, but I would say it happens all the time," says Malcolm Walls, of the nonprofit Mississippi Action for Community Education (MACE), echoing the comments of several other community leaders as well the state's chief archaeologist, Sam McGahey. Some farmers don't know about the old cemeteries or mistakenly consider them abandoned, says James C. Cobb, a history professor at the University of Tennessee, author of a book on the Delta, The Most Southern Place on Earth. In other cases, Cobb says, the problem stems from "not putting a high premium on the places where black people are buried."

Just in the area near Bamboo plantation, people talk of two or three other cemeteries now plowed and planted. "It really does seem bad, but they sure do it," says Martha Thomas, 61, whose husband, A.T., was once the pastor at the Bamboo plantation church, Mount Olive Missionary Baptist, and now serves a nearby church. But Mr. Ware and his parents are among the first to take action. They filed a lawsuit last fall against the owners and farmers of Bamboo plantation, seeking $15.5 million in damages. They hope the suit will, at a minimum, deter other cemetery destruction. "It was only half an acre of land," laments Mr. Ware, 34, who was raised at the Mount Olive church and is now pastor of two others. "All that desecration for a measly half an acre."

In answer to the suit, the owner of Bamboo plantation - Shady Bayou Farms Inc. - contended no cemetery was ever located on its land. So did farmers who have leased and worked the land since 1988. Still, the farmers went ahead and planted cotton for another season on the graveyard site - after the suit was filed and churchgoers had been quoted in the local newspaper saying their relatives were buried there. Asked about that second planting, the attorney for the farmers, Richard G. Noble, said his clients, who have lived three miles away from the cemetery all of their lives, were certain "there was no cemetery there." In court depositions, John Pieralisi said he remembers Mount Olive church but contends: "I have no knowledge of grave sites or markers of any kind on that property." His attorney also points out that there was no deed or registered property map of the cemetery in the county courthouse.

But the Mississippi Department of Transportation's current maps show the cemetery, an official there noted. And state archaeologist McGahey said the cemetery also is prominent on his maps, which were drafted by the U.S. Geologic Survey in 1967. "I don't know why there aren't more people prosecuted on this," he adds. Mississippi law makes it a misdemeanor, punish Mississippi, they've been doing this (desecration) so long I reckon people just figured there was nothing they could do."

That was the issue at old Bamboo Plantation

The plantation is situated in the heart of the Mississippi Delta, that isolated, hard-living land that has produced the soulful music of the blues. The Delta is a spare-looking place where the horizon is endless. The land is flat and farms are big and many people are intensely poor. When it comes to race relations, the Delta is stuck in time. Here, Bamboo plantation is nestled between other former plantations in an area so rural it doesn't have a name. It is past a speck of a place called Dunleith, past a blip called Long Switch, along a gravel road named Bamboo. It was here that Mount Olive Missionary Baptist Church once thrived within a small plantation community.

One of Mr. Ware's earliest memories is at age 7, when his little brother Kenny died of a seizure. Mr. Ware remember mourners and church music and his brother's tiny casket in the green churchyard. "Back in those days, you worked on the farm and you were buried on the farm," says Mr. Ware. "Blacks didn't have the money to be buried elsewhere." The church's last burial was around 1970, for Joe Watkins, an 11-year-old boy who was Mr. Ware's classmate. By then, the church congregation had dwindled. Blacks were moving to bigger cities in search of better jobs. And field work was becoming so mechanized that farmers were employing fewer and fewer people. That's when Mount Olive church merged with nearby Pleasant Valley Missionary Baptist Church, where the Rev. Thomas also was pastor. Ten years later, the empty Mount Olive church was sold. And - as so often happens in Mississippi - the buyer carted the building off to a new location.

Moving the Church Left the Burial Ground Vulnerable

As years passed, weeds grew tall in some areas and brush collected in piles, but an oak tree and a few smaller saplings still formed a shady landmark on the endlessly flat horizon. There were a handful of tombstones in the cemetery; most graves were designated by metal markers. On March 21, 1988, Tom Cooper, an agronomist who lived in the area, was visiting the cemetery with a friend. Cooper noticed the cotton fields were narrowing in on the graves. The largest headstone was toppled over and gouged by a farm implement. Cooper read it with interest. "It said 1940 to 1959, and it said Manuel Williams," he remembers. "I was born that same year and I remember thinking, 'Gosh, I've already had 30 years more than that boy had.'" Copper wrote his impressions in a diary. He called a news reporter, who took photos, but a story was never published.Reverend Ernest Ware first told Skip about the destruction of Mount Olive Cemetery on July 20th, 1991. Upon witnessing how difficult it was for the reverend to explain the total lack of respect for black cemeteries in the Delta, Skip immediately "decided to do something about it." He hired a young attorney from Clarksdale named Walker Sims, and pledged to see this battle through to the end. While it seemed that the lawsuit might be forgotten, "time and time again," he spent an estimated $4,800 to keep it moving forward albeit slowly for six years. His financial backing and tireless effort stemmed from his desire to restore the hallowed burial ground and re-constitute the graves at Mount Olive.

|

| Rev. Ware standing next to the former Mt. Olive Cemetery |

Cooper returned to the cemetery in early 1990, but it was gone. All the stones had been pulled up and the site demolished. Rev. Ware noticed, too--on the very Sunday that he decided to show his four children, ages 6 to 12, where his own little brothers were buried. "I just couldn't believe it was gone," he recalls. "Everybody knew it was a graveyard; it was there since the 1930s." One day in June 1990, a plantation worker told Cooper straight out that he had been ordered to remove the tombstones.

Cooper called the sheriff, but nothing was done. Then came planting season. Cotton seeds were sown into the graves of children and grandmothers and people who had lived their lives cotton-poor and cotton-oppressed. Some of the older church members felt nothing could be done. Pastor Thomas "thought it wasn't right, but he had seen it many times, so he wasn't surprised," says his wife, Martha.

Cooper called the sheriff, but nothing was done. Then came planting season. Cotton seeds were sown into the graves of children and grandmothers and people who had lived their lives cotton-poor and cotton-oppressed. Some of the older church members felt nothing could be done. Pastor Thomas "thought it wasn't right, but he had seen it many times, so he wasn't surprised," says his wife, Martha.

|

(Greenville, MS) Delta Democrat Times

November 10, 1991, p.1.

|

The newspaper in Greenville wrote a story, but nothing came of it, that is, until the dedication of a memorial for Charley Patton, the legendary king of the Delta blues, at New Jerusalem Missionary Baptist Church in Holly Ridge, Miss., where Mr. Ware now serves as pastor. After the ceremony, folks from the music industry started chatting about how headstones in Mississippi are sometimes destroyed. "Not just headstones," Ware exclaimed, "whole cemeteries...they did it to my brother."

People were shocked. "I grew up in a town where Revolutionary War guys were buried (Rahway, N.J.), and I thought cemeteries were forever," recalled Raymond "Skip" Henderson, a New Brunswick, N.J., guitar-store owner who had helped arrange the Patton memorial. "This was mind-boggling," he said. "Children's graves turned into cotton and soybeans?" So started the legal action. In addition, Henderson and others are looking into how to tighten the Mississippi law governing cemetery desecration. "I'm trying to get justice, respect, that's all," Mr. Ware says. "The most important thing is to stop the cemeteries from being plowed under.

The Conclusion of the Case

By T. DeWayne Moore

|

| Skip Henderson, letter to unidentified party January 28th, 1997, MZMF Files. |

The defendants never admitted any wrongdoing, but they did settle the lawsuit for an undisclosed amount of money. The award, however, came with no stipulations as to the use of the settlement money, and the family decided not to reconstitute the abandoned burial ground. This development left Skip "deeply saddened," because not only did it appear that he now had to beg to recoup his investment, which the MZMF loaned to cover the costs of the lawsuit and recover the cemetery, but he also realized that the family had abandoned its original intentions of restoring, what Skip maintained was, such a "holy" plot of earth. "These are not my relatives," he explained in a letter following the settlement; "they are yours," your family members, he implored, encouraging the family to remember "them and act on that memory." In addition, Skip requested that Rev. Ware donate one-tenth of the settlement to the Mount Zion Memorial Fund, partly to reimburse him for his investment and partly to fund the restoration of the Mount Olive Cemetery. "Please take a moment to look into your hearts," he pleaded:

and "consider what has happened here...For the first time in the history of the State of Mississippi, Black people have won a victory of this great importance over White cotton farmers. Will you not use some of the proceeds of this lawsuit to rebuild the Mount Olive Cemetery? Please remember that the graves of your family members can be honored once again as a place of rest in the Holy Spirit. [But only] if you choose to do the right thing, without further delay."

He never recouped his investment or re-established the cemetery, which indeed left a bitter taste in his mouth. The experience had opened his eyes, however, to the doubly-dangerous environment that notions of racial difference had created in the Mississippi Delta. The prevalence of almost all-black residential communities, schools, and organizations and the continuance of a racial discourse among had proffered a contentious social climate in the mid-1990s. Even though mechanization had displaced scores of black farmers and the civil rights movement had allowed some blacks to experience upward mobility, the major Delta cities swelled in population, inviting the ragged and poverty-stricken to settle in their ill-equipped municipalities. The poor economic outlook in the 1990s also ushered in riverboat casinos to the Delta. The legalization of casino gambling was not, however, the economic cure-all that many hoped it might become over time. The performance venues inside the casinos did an excellent job of putting several local bars and men's clubs out of business. Several of the surviving jukes on Nelson Street in Greenville closed their doors in the late 1990s, because it was hard to compete with free drinks, nationally-famous entertainers, modern sound-systems, and auditorium-style seating.

The social worker and guitar dealer from New Jersey had come to the black communities of the Mississippi Delta, which "swallowed him up," as one colleague put it, perhaps even blinded him, to his own precarious role as an outsider and activist. His mission as well as his increasingly frequent encounters with the widespread effects of disrespect and denial forced him to trust strangers who cared very little as to why he had come to the Delta, or why he had setup a conduit to rural church communities no longer in existence. He came to realize that his hopes of reconstituting abandoned burial grounds was never really shared by his clients, who, in fact, held great power to undermine such an effort. Mt. Olive Cemetery remains to this day afield of row crops indistinguishable from the rest of the field. This would not be the last disappointment, nor would it be the last time he misjudged the motives of his clients. Skip mushed on, nevertheless, with somewhat of a devil-may-care attitude. His mission remained intact and unchanged....

Donna St. George, "In the Delta, Blacks' Cemeteries were Plowed Under, Planted Over," Philadelphia (PA) Inquirer, November 14, 1992.